at the 2013 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty pegged the value of even a third of the port trust land at a staggering Rs 1.25 lakh crore.

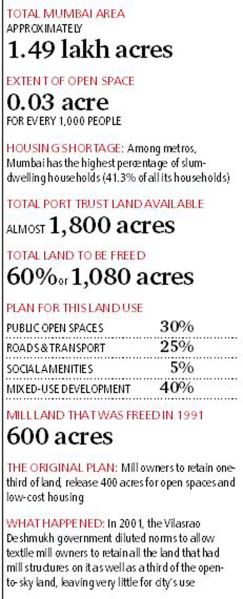

The Mumbai Port Trust (MbPT), known for tenaciously holding on to its under-utilised land bank, will streamline port operations and shut down some of the polluting and loss-making activities. It will then release 60 per cent of the land, i.e. 1,080 acres, for the city’s use, to decongest its choked streets and infuse the cityscape with fresh green lungs. There will be public-private participation, with an initial corpus of Rs 1,000 crore to be raised by Maharashtra and the Centre.

The idea to utilise unused port land was first mooted by the Maharashtra government in 2002, only to be buried in bureaucratic rigmarole. It got a fresh lease of life when Union Minister of Shipping Nitin Gadkari constituted the land development committee.

Gadkari’s refrain has been, “I won’t give a single piece of land to builders”. After the proceeds of mill land sales went entirely into private coffers, Gadkari clearly knows he has to reassure the city.

And yet, this port land was “excluded from the city’s imagination”, as the foreword by former Maharashtra chief secretary D M Sukthankar to the expert panel’s report puts it. “Finally, everyone seems to agree that the entire land is no longer required for the port’s operational needs. It can be used effectively for meeting the deficiencies in the city’s development plan,” said Sukthankar.

The underlying theme is “Open, Connected and Green”. In other words, the land would be opened up for public use, while ensuring vast green spaces, and connected through transit modes.

While the finer details are yet to be worked out, going by the proposals — an amalgam of suggestions by government agencies and citizens’ groups —Mumbai may become the first Indian city to re-imagine its docklands for such use.

***

Under the plan, 30 per cent of the freed land is to be reserved for parks, playgrounds and other such breathing spaces — open spaces in the city amount to 0.03 acre for every 1,000 people currently. Another 30 per cent would be earmarked for roads, transport facilities and social amenities. The rest will be for mixed-used development such as zones to promote entrepreneurship, strengthening of fishing industry, office and retail market and a finance centre.

“We have tried to preempt any repeat of the mill land sale where almost everything was appropriated for private use,” says a panel member.

Mumbai, which has three north-south mass transit corridors in its Western, Central and Harbour railway lines, could get three additional ones in the form of a Bus Rapid Transport System, an underground metro line, and intra-city and inter-city transport. The eastern waterfront will be made more accessible through sea-side promenades and cycle tracks. New tourism facilities are proposed to be developed around the water theme. There’s also a plan for a London Eye-like ferris wheel, to be called Sudarshan Chakra. Marinas — docks to handle small yachts or boats — are proposed to replace the docks that once handled cargo vessels.

Special emphasis would be laid on heritage and ecology conservation.

For a city whose speculative real estate puts houses beyond the reach of most people, there is a mention, though cursory, about creating modest-sized social housing in addition to the reconstruction of workers’ quarters and shanties. These low-cost homes and rental units will cater mainly to those working in the new jobs expected to be generated on this land.

Narinder Nayar, a member of the land panel and chairman of Bombay First, a businessmen-led urban transformation think-tank, points out that the last time large green spaces were created in Mumbai was more than 100 years ago by the British. “At the time of Independence, Mumbai’s population was 1.5 million; it is 12 million now but the open spaces have shrunk greatly. The bad planning of mill land development has worsened the traffic density in Mumbai. The 1,000 acres of port trust land once again presents a tremendous opportunity.”

***

Of the other cities in the world to use their docklands is Melbourne, which has done so to expand its commercial business district, and Sydney. London Docklands, which was once the world’s largest port, has reinvented itself into a residential and commercial hub linked to the city by the Docklands Light Railway. Cardiff, Rotterdam, Liverpool, Baltimore and Boston have all re-united their city centres with their port land for uses ranging from social housing, retail and international finance centres to creation of cultural, recreational and tourism hubs.

However, no other city had the unique complexities of Mumbai. Its port land is a labyrinth of encroachments, both by slums and corporate houses, derelict properties and polluting activities. It also has spawned demands from multiple claimants ranging from citizens’ groups to various government agencies.

For instance, MbPT trade unions are up in arms against any move to create helipads and marinas at the cost of trimming port activities. Fearing loss of jobs, the union wants homes at construction cost for its 11,000 employees and 36,000 pensioners on 122 acres of land that currently houses 7,000 workers’ quarters.

“In 2013-14, we managed a turnover of 60 million tonnes of bulk cargo, but to make available land for their many plans, MbPT is slowly diverting loading and unloading of cargo to the Kandla port in Gujarat,” says Maruti Vishwarao, secretary of Mumbai Port Trust, Dock and General Employees’ Union. He adds that while the unions are not opposed to releasing some of the land for the city’s needs, the revenue generated should be ploughed right back into the port trust’s coffers. “After all, the Mumbai port has existed since 1873, much before the financial city that Mumbai is now.”

Sulakshana Mahajan, an urban planner with the state government think tank Mumbai Transformation Support Unit, points out that the decline of port cities all over set in a few decades after the end of colonialism. Port activities decelerated further with increasing containerisation, which the traditional ports were ill equipped to handle. “Unlike Mumbai, most western cities were quick to consolidate their port activities and let go of what was unviable in order to release the additional land,” she says.

Mahajan further points out that as far back as the 1980s, then prime minister Indira Gandhi had directed the MbPT to release its surplus land for public amenities as soon as the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust in nearby Navi Mumbai became fully operational.

***

Of the total 1,800 acres with the MbPT, only 23 hectares is actually vacant, and that too is scattered all over.

Take the Sewri fort. Under the plan, it would be restored to serve as a viewing gallery for a flamingo park to be created down below. For now, the view from the fort is of withering coastal mangroves on slurry, splattered with pink patchworks where the flamingos have flocked. From the Rann of Kutch they come here to feed on algae soaked in toxic effluents, waste from the nearby ship-breaking yard and sewage from a municipal outlet.

The sky to the north is lined with thick smoke emanating from three oil refineries, a coal-based power plant and a chemical fertiliser plant. In the southern-most tip of Sassoon Docks, a hub of fish trade worth a couple of crore rupees daily, the land is covered with fish-scales and offal. At the fishermen’s colony, 62-year-old Kamlakar Vaity is more worried about his granddaughter’s daily battle with bronchitis than hisown. “She is only three and has to be put on nebuliser often,” he sighs.

For the last six years, lakhs of tonnes of imported coal has been arriving at the port land to fuel Mumbai’s power plants. From the giant stacks that sporadically combust due to the heat, the coal is ferried in open wagons and dumpers that carpet the worn-out roads with soot. All along this stretch are virtual ghost towns of crumbling housing quarters, run-down warehouses, iron scrap yards and rows of tarpaulin or corrugated roof shanties. Then there is an urban cesspit of two dozen slum pockets housing at least 1.5 lakh residents who are worse off than their counterparts elsewhere in the city.

Most of the people who live in these quarters are informal sector workers, employed in the scrap yards, warehouses, ship-breaking and repair units.

Since all this land belongs to the port trust, the slums could never get the civic body to provide them any facilities. Kawla bunder’s 40,000-odd residents share two unusable toilets. Water is collected on the sly from nearby fire brigade tankers, through hoses passing through raw sewage.

The land development panel has been emphatic on the need for a policy on the lines of the Rajiv Awas Yojana, which will involve a survey of all slum residents, housing them with security of tenure, and rehabilitating them in terms of livelihood once the hazardous activities are forced shut. The panel has said that such a policy, to be framed by the MbPT, should not follow the state government’s flawed model of slum redevelopment based on arbitrary demolitions and free housing for those declared ‘eligible’, in return for allowing builders to exploit a part of the land.

However, even before the report is set in motion, officials have started simply effacing the shanties and reclaiming port land, cordoning off the cleared areas.

MbPT Chairman R M Parmar says the port trust is simply doing its job as the prevailing laws allow them to demolish shanties irrespective of how long they have existed. “The Union government is yet to decide on a policy for slums based on the panel’s recommendations. But till that happens, we are allowed to carry out demolitions under law,” he says.

Conservancy worker Senthil Kumar has been battling sleepless nights since the MbPT mowed down hundreds of shanties in neighbouring Powder Bunder. According to him, officials swooped down on the colony at night with a demolition notice, ordering residents to vacate their homes within 12 hours. Typed in English, it was indecipherable to most of the Dalit and Muslim migrants.

“We have been here for three generations now. If I had a home in the village to go back to, I would have taken my family out of this hellhole long ago,” says Kumar, 36.

Fifteen-year-old Aarti Nandkishore doesn’t recall seeing demotions of this scale before. “They seem determined to get rid of the slums this time. I grabbed my school bag and rushed out before the bulldozers could flatten my hut but I have not been able to go to school since,” she says. Her school bag is now kept at a relative’s house, as Aarti and her mother Jamuna forage the ruins of their house for wood to sell for some money.

Other displaced residents continue to live on the fringes of the newly cleared land, banking on hope.

***

The shanties incidentally are not the only encroachers on the prime land. Fifty per cent of it is occupied by lease-held properties, including by a few corporate giants. The port trust’s tenants include Anil Ambani-led Reliance Group, and the MbPT is caught in legal wrangles on the issue with Tata Group’s Indian Hotels Taj Mahal Palace and Tower, Bombay Yacht Club, Radio Club, Hindustan Unilever, among several others.

“Many of these tenants, including corporate houses, have constructed entire buildings illegally or sub-let the property in breach of the lease agreement. The MbPT should go after the bigger encroachers instead of gunning for slum residents,” says Arvind Sawant, the Shiv Sena’s MP from Mumbai-South.

Much of the leases have long expired but are deadlocked in litigation in anticipation of a real-estate bounty whenever the land is opened up for development. Attempts to rationalise the paltry rentals at today’s market rates are also stuck in litigation.

Even once the land has been acquired and hazardous activities such as ship-breaking, handling of rock phosphate and coal are shifted out to ports outside Mumbai, as proposed, the toxicity levels along the waterfront areas abutting it are so high that it will take up to five years for its bio-remediation and for the soil, water and air quality to be restored to habitable levels.

The report also has chapters detailing how to go about getting land back from the lease holders and defaulters, and how to shift out harmful industries.

Across the waters from Powder Bunder, where slums were demolished recently, is the ship-breaking yard of Lakri Bunder in Darukhana. Here, at Plot No. 10, a Bollywood film crew is busy preparing the sets for the next day’s shoot of an Akshay Kumar starrer. The crew goes about assembling heavy metallic props unmindful of workers from the nearby slums, sawing open and dismantling what was India’s first aircraft carrier and one of the heroes of its 1971 war, INS Vikrant.

It may be a little too late in the day to resurrect that ship, but beneath and around it, may lie Mumbai’s last chance to assert its needs on the urban cartography.

– (Courtesy The Indian Express)

![Online [Free Watch] Full Movie Coco (2017)](http://www.realnewsofindia.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/molestation-190x122.jpg)

Recent Comments